Sometimes I think that when we see art that was made in the distant past, we are only able to feel the merest sensation of what it must have felt like to have seen it contemporaneously to its creation. This thought haunted me as I made my way through the spectacular painting show, Van Gogh to Kandinsky, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Those vibrant, outrageous colors made me very happy, but there could be no ‘shock of the new’ to quote Robert Hughes. As I wrote a couple of weeks ago, we have been habituated to colors that bright and brighter all our lives in what we are used to seeing on screen.

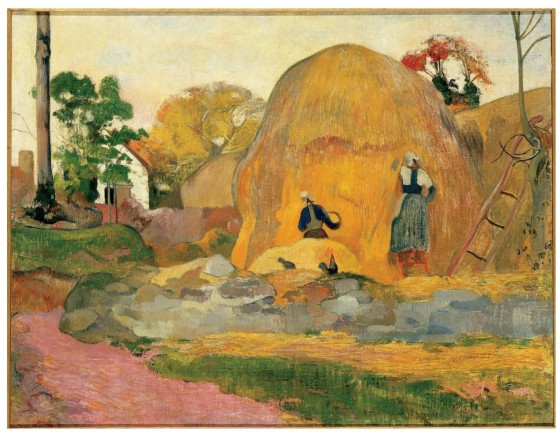

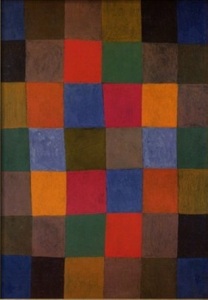

Still, it was interesting to follow the liberation of color during the late nineteenth century up to World War I: first to see how color was just intensified as in the paintings of Van Gogh and Gauguin-still connected to reality just enhanced.

Paul Gauguin French, 1848–1903 The Yellow Haystacks, 1889 Oil on canvas Paris, Musée d’Orsay, gift of Mme Huc de Monfreid, 1951 Photo © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, NY.

T hen it was allowed to take off, tentatively attached to semi-abstract images as in Robert Delaunay’s (1885-1941) Red Eiffel Tower (1911-1912) New York, Solomon Guggenheim Museum.

hen it was allowed to take off, tentatively attached to semi-abstract images as in Robert Delaunay’s (1885-1941) Red Eiffel Tower (1911-1912) New York, Solomon Guggenheim Museum.

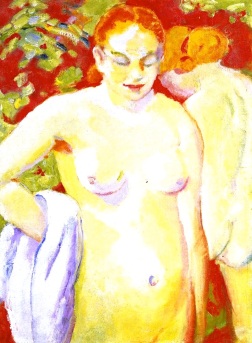

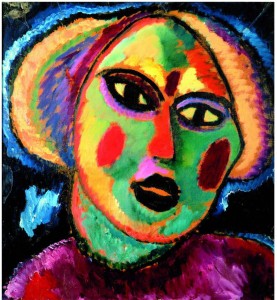

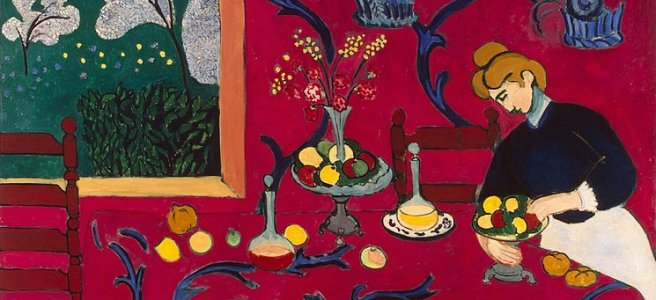

Color was made to stand in for the painter’s feelings, (a visual example of what Kandinsky called ‘inner necessity’) though still anchored in the visual world (as in the painting below)

Alexei Jawlensky, Russian, active in Germany, 1864-1941,

Girl with Purple Blouse, 1912 Oil on paper mounted on canvas, Cologne, private collection);

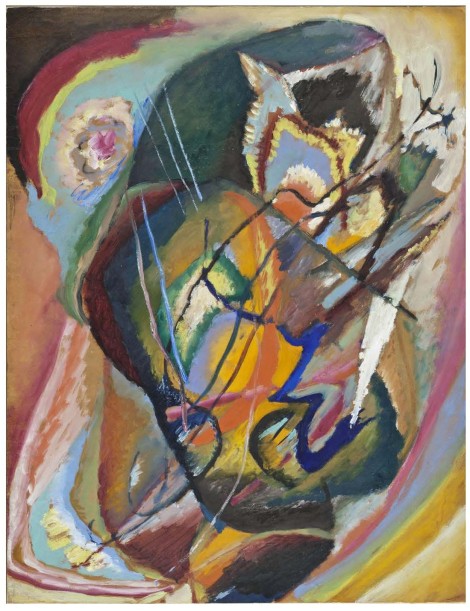

and finally inexorably it was left to stand on its own, sometimes in some type of relationship to the image, sometimes not.

(Wassily Kandinsky Russian, active in Germany and France, 1866–1944 Untitled, Improvisation III, 1914 Oil on cardboard Los Angeles County Museum of Art, museum acquisition by exchange from the David E. Bright Bequest © Estate of Wassily Kandinsky / SODRAC (2014) Photo © Museum Associates / LACMA)

The show clearly traced the movement of ideas about color and expressionism through the efforts of contemporary gallerists. It was exciting to follow the discourses that ran from Van Gogh to Cezanne to Kirchner to Kandinsky, and so on. Certainly, as a painter, I would like to believe that artists revolutionize the way people see, but artists are embedded in their time period, even painters like Van Gogh who was marginal during his lifetime. And at the end of the nineteenth century, certain non-art developments in the society helped this freeing up of color for painters. The big thing was the invention of premixed paints in tubes, a new expanded selection of vibrant light-fast colors that did not have to be hand made by the artist. This was part of a larger color revolution in chemical technology.

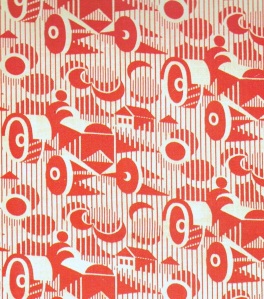

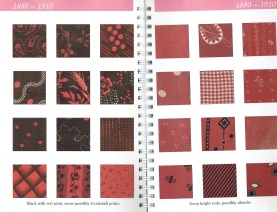

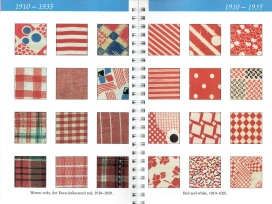

Regina Lee Blaszczyk in her book, The Color Revolution writes about the invention and development of chemical dyes that took place in France and then Germany, with Germany winning the lion’s share of the market for synthetic dyes. These dyes created a huge range of colors which were organized into swatches for the clothing market. Again, the idea that color could be separated from the object and chosen on its own merits was abroad in the society. And there was a lot more and brighter color to be seen in clothing and advertising at the same time that color began to be central to the avant garde. I don’t think that this is a coincidence! I also wonder if the fact that electricity came in to general use at this time might have changed the way that people saw color.

Of course, it is a two way street, and the cutting edge artists influenced fashion, markets, design, and many other visual expressions of the society. Next week, I will be looking at Georgia O’Keefe an American artist who influenced color during the same early Modernist time period.

Meanwhile, if you are in town, the show Van Gogh to Kandinsky is on at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts until January 25th. It is a great antidote to this bitter cold, all white winter weather we have been having!

Color action: I often use color fans from paint companies to match colors in paintings. I note the number of the color chip, and cut a piece out of it to use as a color note when I get home. The chips, I find, are more accurate than colored pencils or markers.

The header for this week’s blog is my own painting, Red amaryllis on acid green ground, which I painted after seeing the exhibit. You can see more of my work at www.floradiem.com.

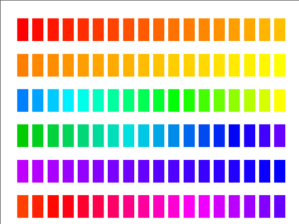

You may have noticed that I don’t use the commonly accepted terms of warm and cool to describe color. It has no basis in science as blue is the hottest part of a flame, and red indicates a cooling star. I think it is more useful to think of a color’s cast in its relationship to either blue or yellow. Cadmium red has a yellow cast. Alizarin Crimson has a blue cast. But since this is a continuum, at what point does the color change from a vermillion to an orange, or from a magenta to a violet?

You may have noticed that I don’t use the commonly accepted terms of warm and cool to describe color. It has no basis in science as blue is the hottest part of a flame, and red indicates a cooling star. I think it is more useful to think of a color’s cast in its relationship to either blue or yellow. Cadmium red has a yellow cast. Alizarin Crimson has a blue cast. But since this is a continuum, at what point does the color change from a vermillion to an orange, or from a magenta to a violet?